Studies Point to Shifts in Cyclone Formation, Intensity; Too Early to Infer Damage, Loss Impacts

By Jeff Dunsavage, Senior Research Analyst, Triple-I (01/24/2022)

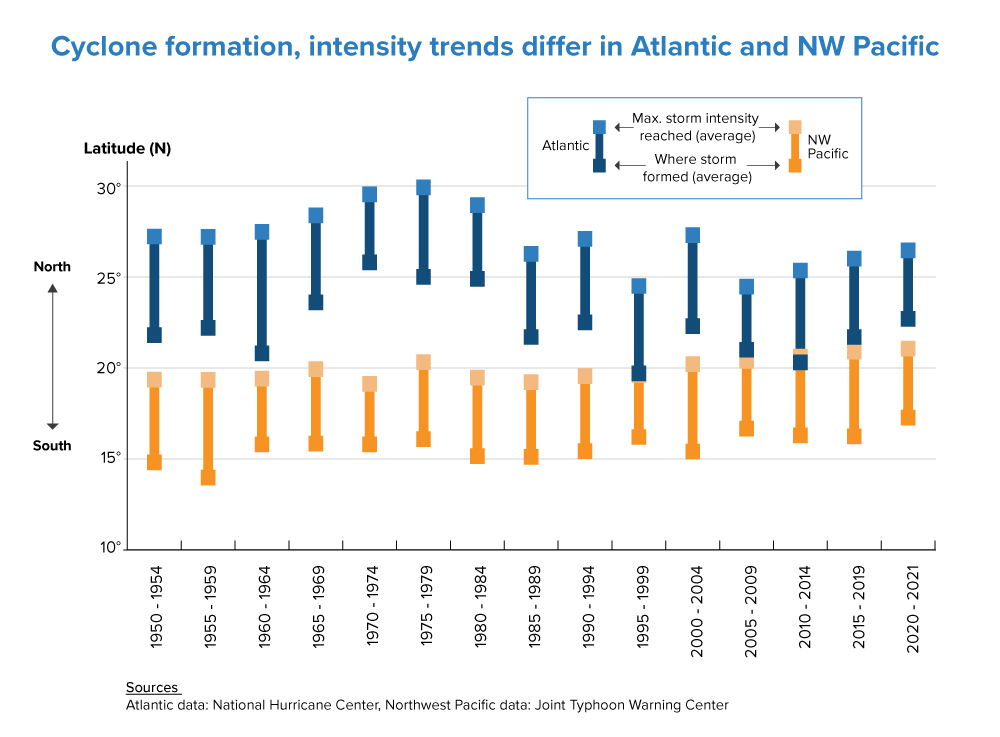

A growing body of research suggests tropical cyclones – known as “hurricanes” in the Atlantic Ocean and “typhoons” in the Northwest Pacific – may be forming and reaching their maximum intensities farther from the equator. In the northern hemisphere, this often puts them closer to major population centers, but Triple-I non-resident scholar Phil Klotzbach cautions against jumping to conclusions about future damage and losses.

“The first paper that came out in 2014 and really got this whole discussion started showed that tropical cyclone lifetime maximum intensity had shifted poleward in both hemispheres, with the strongest signal in the Northwest Pacific,” said Klotzbach, a research scientist in the Department of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State University. He said the authors of that paper “attributed this increase to expansion of the tropics, which likely has a significant human-induced component.”

A more recent paper that investigated lifetime maximum intensity of tropical cyclones, published in Nature Geoscience in December 2021, “cited a whopping 185 references,” Klotzbach said. He added, “It is important to note that we haven’t observed a significant poleward migration in Atlantic lifetime maximum intensity location.”

Joshua Studholme, a physicist from Yale University and lead author of the most recent study, told BBC News that, as the world gets hotter, the temperature difference between the equator and polar regions will lessen, affecting the jet streams that tend to keep hurricanes closer to the equator.

“As the climate warms, that sort of jet stream activity that happens in the middle latitude will weaken and, in extreme cases, split,” allowing cyclones to form further north, Studholme said.

Klotzbach pointed out that a range of variables – particularly, storm intensity and duration – would influence how this trend ultimately plays out in terms of damage and insured losses.

“We currently have not observed a poleward trend in where Atlantic storms form or reach their maximum intensity,” he said. “If this poleward trend did develop, it could mean certain portions of the U.S. coastline would become more susceptible to future hurricanes while potentially reducing the risk to the Caribbean or Central America. It’s just too early to make reliable predictions.”